Are travel influencers ruining your life?

Honest insights from an apologetic influencer, after 500,000 followers and a decade on social media.

She wakes up early, before the sun warms the cobblestones, and rushes onto the deserted streets of Paris. Entire city blocks disappear beneath her marching feet. She barely notices. Her right shoulder aches beneath the weight of her bag, as she frantically looks around. Finally, she sees the silver door with “toilettes” inscribed in capital letters.

With the press of a flashing green button, the door opens and closes behind her with a hiss, like a vintage space shuttle. She covers the toilet lid with paper and sets the bag down. The floor is sticky. Her trainers make an ugly kissing sound as she takes them off, one by one, and replaces them with a pair of high heels. Then she removes her jumper, stuffs it inside the bag and slips a dress over her head. The fabric skims her ankles, concealing the leggings she put on earlier. She inspects her hair in the dirt-specked mirror above the sink and smooths it down, before rushing back outside.

The cold morning air brushes against her naked arms and she bites her lip, which is slowly turning purple beneath her red lipstick. But she is nearly there. The Eiffel Tower looms over her like the skeleton of some primordial being, its bones gleaming against the reddening sky. She heaves her bag onto the lawn and pulls out a spindly three-legged metal contraption. She twists its limbs until it stands upright, attaches her camera and presses her left eye to the viewfinder.

With the critical precision of a deer hunter, she studies the shot. The horse chestnuts are not yet in bloom. The grass is yellowed and sparse, trampled by thousands of feet. Her fingers tremble as she sets the timer and runs into the shot. Her heels sink into the soft ground. Ten, nine, eight. She turns her back to the camera. Seven, six, five. She lifts her arms to make sure they look thin. Four, three, two. She tosses her hair. One.

She repeats the process over and over, running between the shutter and the frame in her grass-covered heels. Afterwards, she sits in a cafe, reviewing the images on her phone and finally choosing her favourite. She erases the couple that had wandered onto the path behind her. She manipulates the colour of the sky until it is cotton candy pink. She uses the blurring brush until her arms look like they belong to a mannequin. Then, with bated breath, she hits share.

The comments are instantaneous. “Goals.” A fire emoji. Three hearts. “This is incredible.” “You are incredible.” She leans back in her chair, bracing herself for the warm flood of satisfaction. But it never comes.

Zooming in on the image she tries to figure out what went wrong. The scene is perfect. Even her hair, prone to limpness, cascades gently down her back. She catches her reflection in a mirror behind her and it makes her shudder. Her curls have flattened. Her concealer has congealed into a grey puddle. Her dress is stained with café au lait. The more praise her image receives, the more detached she feels from the woman on the screen. With her smooth skin and unstained dress, she could be just about any travel influencer. But she is certainly not her. Quietly, the young woman begins to cry.

This image is seared permanently into my brain. I feel sympathy for the weeping girl, for the lengths she pushes herself to for the perfect image. But I’m also embarrassed by her. This is not the soft pang of second-hand embarrassment you can easily shake off. This is a searing I-know-too-much sort of embarrassment - because the woman is me, in 2016.

My Paris moment wasn’t an outlier. Changing in port-a-potties and shivering in summer dresses seemed like a small price to pay for the perfect travel image. But after a decade of working as a social media content creator, known as @girlvsglobe, I feel differently. This essay is my attempt to understand how female travel influencers curate their online selves, why, and how to undo some of the damage these representations cause.

The rich boys’ travel club

Travel used to be a privilege only rarely extended to women. Before mass tourism, there was the Grand Tour, a rite of passage amongst European aristocrats. Beginning in the 17th century, these men followed a standardised route across the continent. The journey typically began in England, continuing through France to Switzerland, before braving the Alps. From there the young men continued to Italy, visiting Turin, Florence, Pisa and Rome before concluding the trip in Naples.

These trips were rarely captured on camera, an impossibility before the daguerreotype’s invention in the 1840s. Instead, travellers were immortalised in paintings and hung them up in their mansions as proof of their worldliness. Italian painter Pompeo Batoni became renowned for his portraits of British noblemen on tour. Most of these prominently featured a white male traveller looking wistfully into the distance, surrounded by antique statues and iconic landmarks. Italy was the picturesque backdrop, but the real subject was the traveller himself.

When pioneering French photographer Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey set out across the Mediterranean in 1842, he became one of the first to capture foreign lands on camera. Compiled in a book called “Monumental Journey: The Daguerreotypes of Girault de Prangey”, his early travel photographs focus on landscapes over people. This was mainly down to the technology available at the time - the daguerreotype process required long exposure times which made it difficult to capture moving subjects.

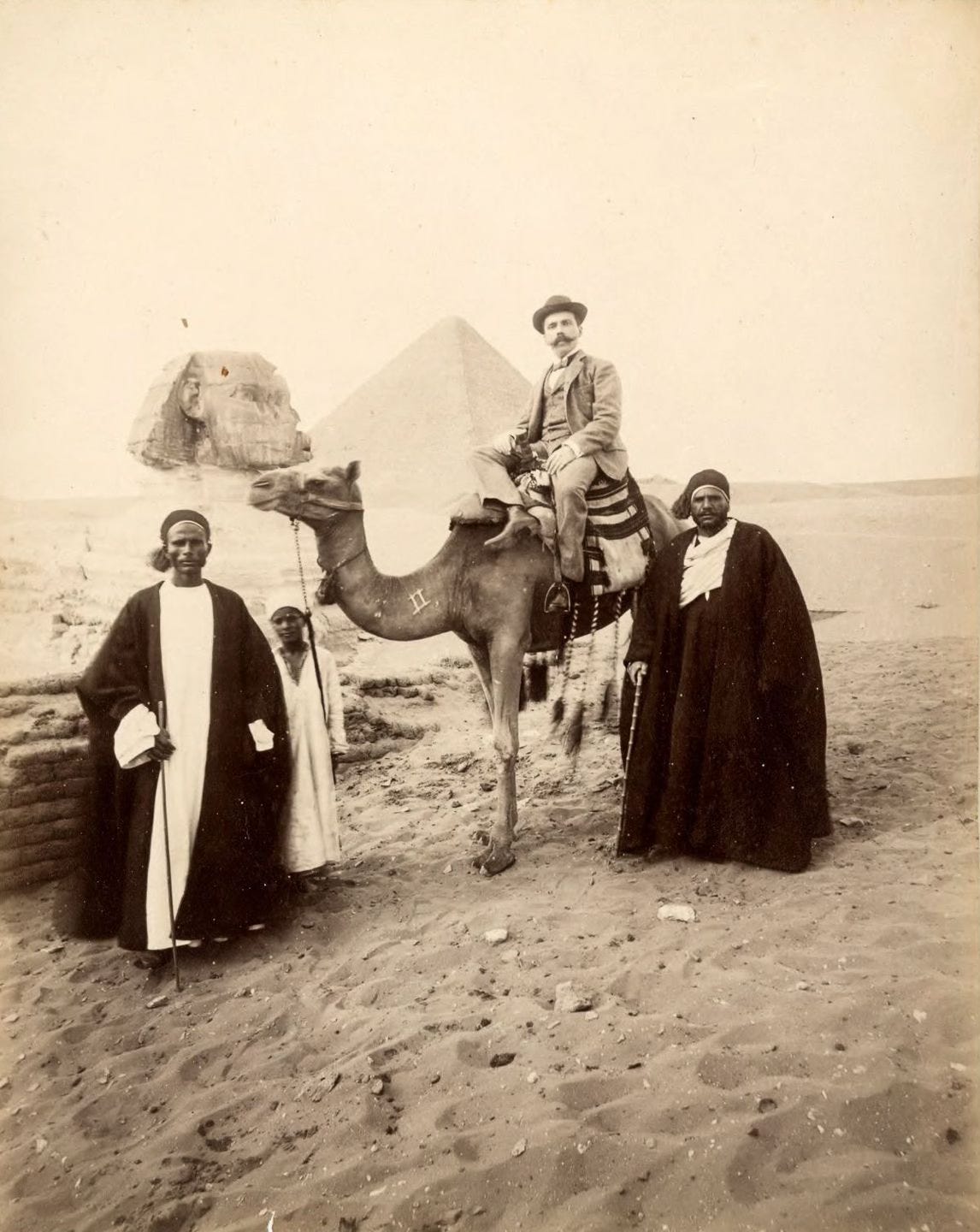

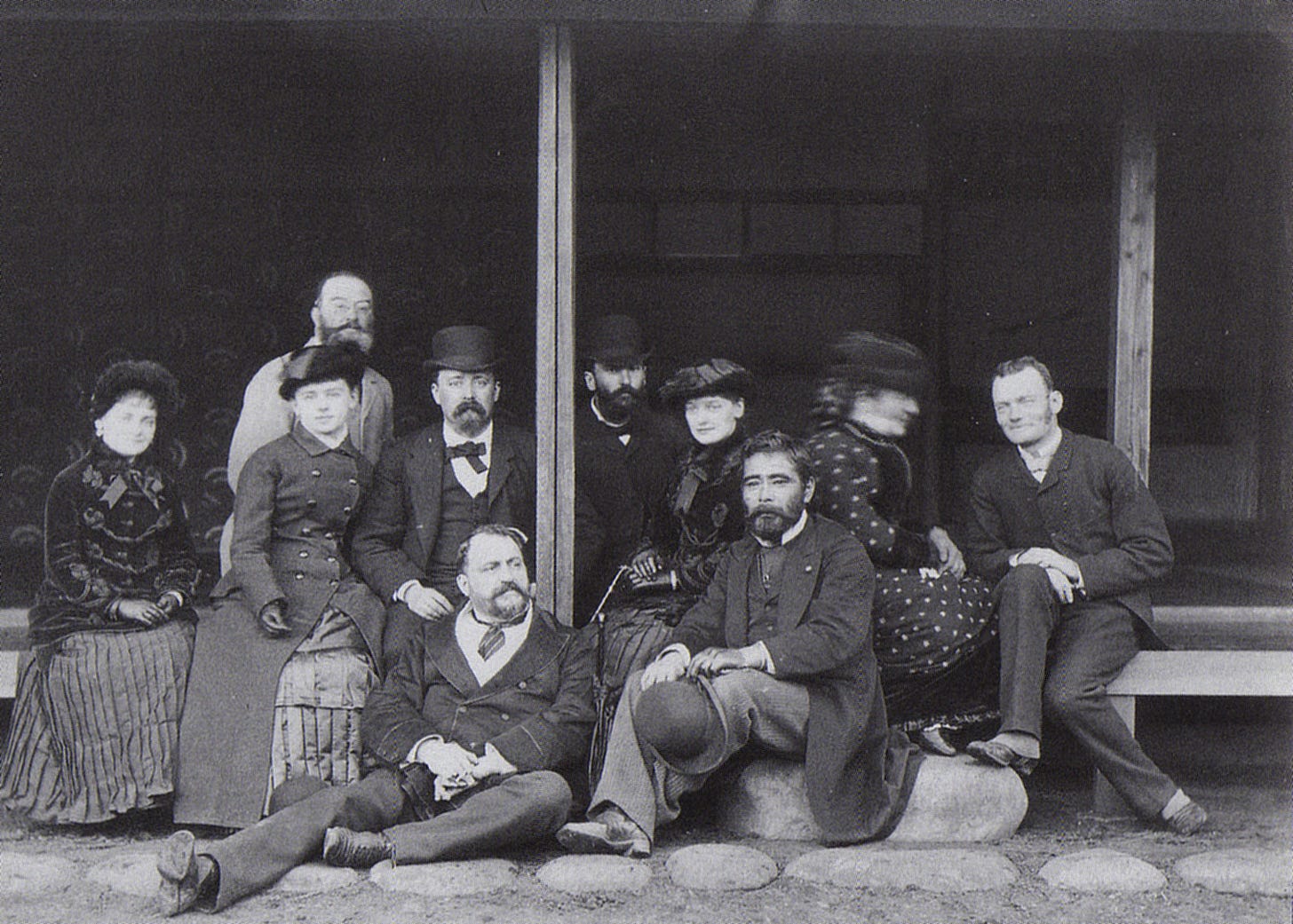

By the 1870s, as equipment became faster and more portable, photographers like the Zangaki Brothers zoned in on the travel industry. In addition to ancient monuments and everyday scenes from Ottoman Egypt, they began to photograph tourists. One example is featured below, with a European tourist posing with local guides in front of the Giza pyramids. Another example, taken in 1882 by Hugues Krafft, features photographer Felice Beato with his European friends and Japanese politician Saigō Tsugumichi.

The Kodak Brownie arrives

At the time of photography’s inception, most travellers were white, wealthy and male. But in the 20th century social norms began to shift. These changes coincided with the release of the Kodak Brownie in 1900. Originally marketed to children, the $1 ($38 in 2024 terms) cardboard box camera quickly achieved broader appeal. More than 150,000 Brownie cameras were sold during the first year of production.

One of the buyers was Gertrude Bell, an Englishwoman born to a wealthy family in 1868. After becoming the first woman to graduate in Modern History at Oxford with a first class honours degree she set her sights on the Middle East. She mapped the region, influenced British colonial policy and, crucially for this essay, documented her travels on camera.

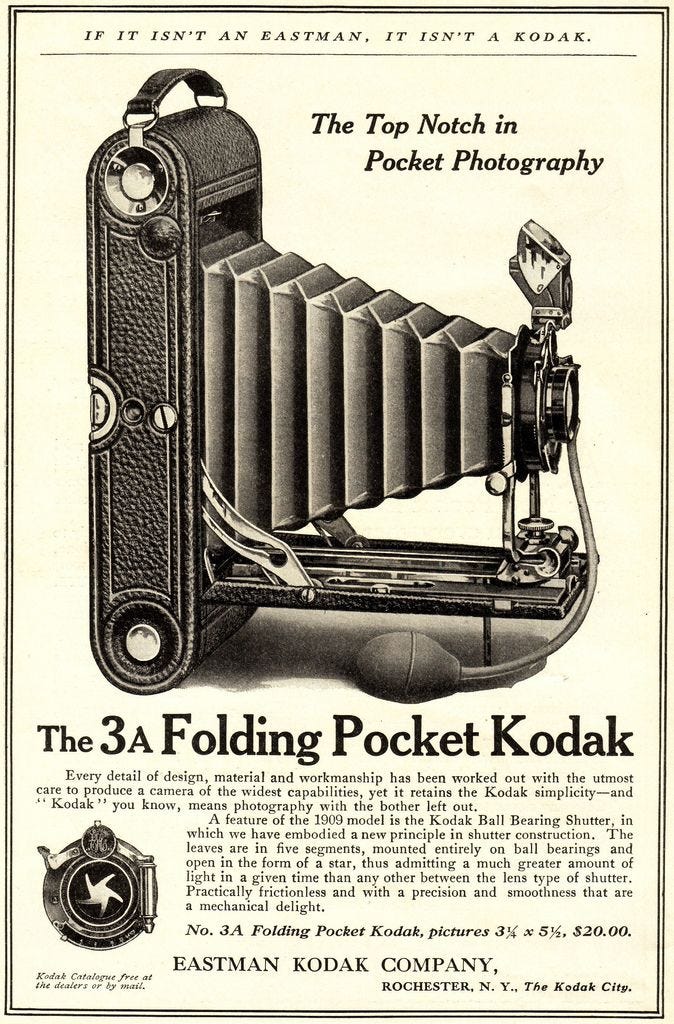

“She carried two cameras where ever she went,” writes Georgina Howell in Daughter of the Dessert, a book about Bell’s life. “One was a hand camera that took glass plates 6.5 inches by 4.25 wide, the other designed for panoramic views.” As specified in another biography, Gertrude Bell: The Arabian Diaries written by Geoffrey H. Taylor, she used a No. 3A Folding Pocket Kodak. Although far from pocket-sized by today’s standards, the camera allowed Bell a degree of portability and spontaneity. Thanks to this technology, we not only have images taken by Gertrude Bell but of her.

Bell’s inclusion in these images wasn’t accidental. Howell explains: “Bell took photographs of herself, as well as of the world around her, because she wanted to record her own participation in the history she was helping to shape”. Bell was deliberately taking credit for her work. As Howell remarks, she “was determined not to be a passive tourist, but a woman who was shaping the future of the countries she was visiting”.

Bell wasn’t alone. Fanny Bullock Workman, a pioneering mountaineer born to a wealthy Massachusetts family in 1859, also documented her travel achievements in photographs. A supporter of the feminist New Woman movement, which emerged on the cusp of the 20th century, she wasn’t satisfied with the role of passive companion to her husband William. One of her most memorable travel images was taken in 1909 and shows Workman reading a newspaper at 21,000 feet - then a record-breaking altitude for a female climber. The headline “Votes for Women” is clearly legible on top.

Less privileged women join the party

Both Gertrude Bell and Fanny Bullock Workman had been born into extreme privilege. But working class, Black, Latina and Indigenous women gradually adopted photography in the ensuing decades. Finding an appropriate case study wasn’t easy because travel photography of this era - and this social group - was mainly intended for private, not public, consumption.

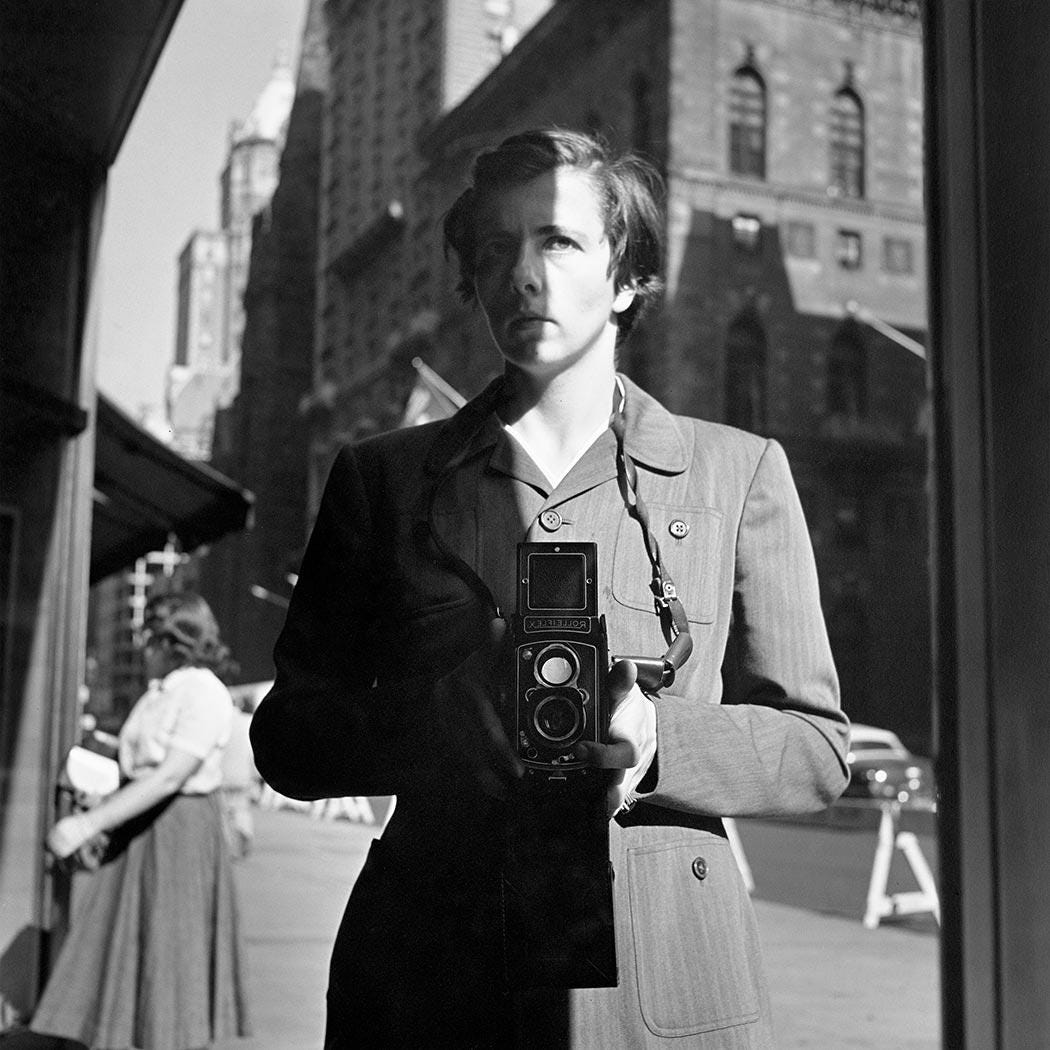

Then I found Vivian Maier. Her photography was never published during her lifetime and its discovery was accidental. In 2007 Chicago collector John Maloof acquired some of Maier’s photographs at an auction and uploaded them to Flickr. The images went viral and were subsequently exhibited around the world, to great public reception.

John Maloof provides this description of Maier on his blog: “Vivian came here from France in the early 1930s and worked in a sweat shop in New York when she was about 11 or 12. She was not Jewish but a Catholic, or as they said, an anti-Catholic. She was a Socialist, a Feminist, a movie critic, and a tell-it-like-it-is type of person. She learned English by going to theaters, which she loved. She wore a men's jacket, men's shoes and a large hat most of the time. She was constantly taking pictures, which she didn't show anyone.”

Maier managed to save enough money to travel to destinations like the Philippines, Thailand, China, Egypt and Italy, before becoming destitute in old age. She produced a mix of street photography and self-portraits, mainly taken on a Kodak Brownie or a Rollieflex 2.8F.

The images were deliberately composed, but not in the way that has since become prevalent amongst travel influencers. Maier didn’t idealise her appearance. She didn’t smile, pose or wear extravagant clothing. Although she features prominently in her photographs, she is rarely the sole focal point. Her travel images position her as part of the world but never reduce the world to a decorative afterthought.

Middle-class travel photo albums

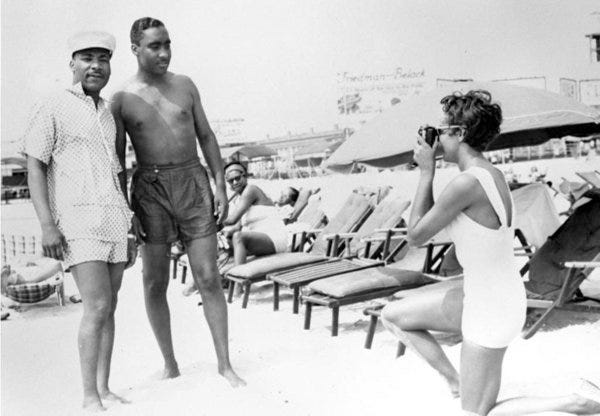

By the 1950s, travel photography had become commonplace. In wealthy Western countries like the United States it stopped being an elite pastime and became increasingly open across lines of class and race. Although Vivian Maier was unusually prolific and creative, her hobby was far from unique.

Early travel photographs by the likes of Joseph-Philibert Girault de Prangey were explicitly intended for public distribution. Their value lay in their educational rather than sentimental qualities. Gertrude Bell and Fanny Bullock Workman similarly created images for the public and featured them in their travel books. Vivian Maier was the first example on our list of travel photographers whose work remained private - until after her death, anyway. As a reminder: “She was constantly taking pictures, which she didn't show anyone.”

Most vacationers in mid-20th century America were less secretive. Travel albums were a private way of preserving beautiful memories, but also a burgeoning status symbol. Writing for The New York Times in 1953, sociologist Robert Lynd put it well: “Vacations, once a rare privilege of the rich, have become a necessary part of the middle-class existence. Today, it is the mark of a family that has reached a level of comfort and stability.” This is echoed by sociologist Dean MacCannell in his book The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class, published in 1976: “Tourism has become one of the most important means by which people are able to demonstrate their social status and differentiate themselves from others.”

Travel albums became an aspirational marker of middle-class success. They became essential to keeping up with the Joneses, a way to demonstrate our accomplishments to neighbours, friends, acquaintances, family members and colleagues.

Fast forward to the 2020s

The travel albums of mid-century Americans were shared outside the immediate family, but only with people one knew personally. The Internet changed that. In 1991, the World Wide Web was launched. In 1998, Google came along. By 2010, Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Instagram and the iPhone had all launched. The private sphere was rapidly bleeding into the public. I experienced this shift first-hand and in real-time.

I joined Facebook in 2007, a young teenager eager to bond with her peers after moving to a new country and new school. Our generation was the first to digitally document every social event, sometimes posting multiple photo albums of a single night. These were shared with friends and acquaintances online, but only rarely outside our social circles.

I joined Instagram in 2013, as an artistic outlet for documenting my university life. It was my attempt to assert myself as a person worth knowing. At the time I was studying political science in London, an insecure teenager lonely and alone in a new country once again. Instagram offered a welcome buffer. I found social interactions much less intimidating from behind a screen, with time to carefully curate my words and images. I wasn’t interested in reaching strangers. I just wanted to feel seen for who I was - or a slightly improved version - by people I knew.

My goals shifted in 2015 when I switched my Instagram account from private to public. I had started a travel blog called Girl vs Globe a year earlier and as it gained popularity, branching out to social media was the obvious next step. Suddenly, my audience expanded from hundreds to potential billions. No longer content with just impressing my friends, I wanted to impress the world.

I became hyper-fixated on growing my audience. Studying the most popular travel Instagrammers revealed a clear pattern: a young, predominantly white, woman wearing a flowing dress, gazing at a photogenic sight with her back to the camera. The destination was secondary, a series of interchangeable backdrops. The influencer was the focal point. And I was happy to follow this tried-and-tested aesthetic if it allowed me to travel.

Creating the perfect image became an obsession. Travel photographers of the 20th century had to be judicious with their shots. Rolls of film cost money and developing them cost time. By the 2010s, technology had removed those constraints. I took hundreds of images at each location, frequently running out of storage on both my camera and smartphone. Between shooting, image selecting, editing and caption-writing, a single Instagram post could easily take me seven hours to produce.

My strategy worked and my account grew. Brands began to approach me with paid work offers. I travelled to dozens of countries. I didn’t earn much money, but my lifestyle was heavily subsidised by tourism boards covering all my expenses.

But although my life looked full of joy from the outside, I felt increasingly empty. My excitement for social media curdled. It all came crashing down on my 25th birthday, amidst a breakup and dwindling self-esteem. In October 2018, I quit social media. There were several reasons behind my departure, but chief amongst them was a fear that I was harming other women.

Female empowerment! Oh wait…

I was right to worry. In her book, Beauty Sick: How the Cultural Obsession with Appearance Hurts Girls and Women, Dr Renee Engeln describes the pitfalls of aspirational online images. She identifies a link between high social media consumption and increased social comparison, greater investment in appearance, heightened self-objectification and a stronger desire for plastic surgery. I had unknowingly been making women feel insecure with my manufactured vision of travel that required hours of preparation. The result felt unattainable, even to me.

My initial concern wasn’t born of academic studies. It was born of the pit in my stomach. Despite knowing precisely how these social media images are created - the planning, styling and editing that goes into them - I constantly compared myself to my influencer peers and judged myself for falling short.

For a long time, I had believed that showing women one of their own travelling the world was the epitome of female empowerment. I wasn’t the only woman with this vision. Travel influencing is dominated by women, in many ways. When searching #travel on Instagram the results skew female. But that doesn’t mean it benefits us all.

The industry’s most visible creators are white women who neatly fit society’s beauty standards. Having attended dozens of press trips throughout my career, it is not uncommon for them to be solely attended by pretty white women. I am one of them and am fully aware that this privilege has helped me grow on social media.

That is not to say that women are only successful on social media because of their looks. This line of reasoning is frequently weaponised by misogynists: “People only follow you because of your looks.” That is reductive and incorrect. Social media is incredibly competitive and appearance alone will not make you successful. But it is a contributing factor.

Privately, travel has never been about appearance to me. I prefer shabby homestays to luxury resorts, I prefer paper plate street food to Michelin-star meals, and I prefer meeting locals on a level footing instead of being waited on by them. My Instagram painted a different picture, one that I thought others wanted to see. In my photos, I was the model of travel brochures - hair coiffed, outfits curated, face lit up with a permanent 100-watt smile.

I looked like I was having the time of my life. But I wasn’t. Not always. My photographs were a performance - sometimes enjoyable and sometimes not - which I put on in order to continue my real travels outside of them. My content may have seemed empowering at first glance. But it did not feel like it, not to me and not to those consuming it.

But are social media photographs really more damaging than their historic predecessors? After all, the Instagram aesthetic isn’t far removed from the Grand Tour portraits commissioned by young 18th-century British aristocrats - a white young privileged traveller in fashionable dress looking into the distance, surrounded by regional artefacts. Both images are the results of a laborious process. Both are intended to clinch the subject’s status as worldly, sophisticated and adventurous. Once completed, both are hung up in galleries - one inside a grand aristocratic mansion and the other on the Internet.

And yet, something has changed. I have identified five key differences between present-day travel influencer photographs and their predecessors. They are scale, editing, attainability, self-presentation and algorithmic reinforcement. In the final section of this behemoth essay (thank you for sticking with it!), we’ll investigate these factors in detail.

The five differentiators

Scale is the most obvious differentiator, and requires the least explanation. Grand Tour portraits were displayed in private mansions, seen only by select guests. Travel photo albums of the 1950s were shared with friends and family in person. Facebook travel photo albums of the 2000s were seen by a wider circle of friends and family, online. But Instagram images posted on public profiles can be seen by any user. For context, as of 2025, the platform has more than 2.4 billion monthly active users.

Most images never reach even a fraction of that audience. But those posted by large travel influencers can easily reach millions. My content has shifted away from idealised travel imagery but still offers helpful numerical context - with little over 500,000 followers my monthly reach hovers between 10 and 20 million views. The ubiquity of influencer images makes their effects more pervasive than the travel photographs of previous eras.

Editing is another differentiator. Grand Tour portraits were idealised, but not to the extent seen today. Researchers from City, University of London found that 90% of 175 surveyed young women and non-binary people filter or edit all of their photos before posting them online. This encompasses ”evening out skin tone, whitening teeth, reshaping jaw or nose lines, and even shaving off some weight”.

The effects of such images were examined in a 2024 survey of girls aged 11-21 years old by Girlguiding UK. The report states that “relentless exposure to edited images leads girls and young women to feel they need to change the way they look”. They found that 54% of respondents wish they looked like they do with social media filters and that 36% feel pressure to use filters. That latter figure rises amongst marginalised groups, with 41% for girls in high-deprivation areas, 46% for LGBTQ+ girls, 48% for disabled girls, and 50% for neurodivergent girls.

This type of editing is problematic in other, more nuanced ways relating to class and race. The Eurocentric beauty standards prominent on social media further marginalise those who do not fit their narrow criteria. This topic deserves a deeper dive in a separate essay, one I would love to write in the future.

The third differentiating factor is attainability. Grand Tour portraits were aspirational but also widely understood as an elite status symbol reserved for aristocrats. Similarly, women like Gertrude Bell or Fanny Bullock Workman were seen as outliers. In her Alpine Journal, Workman wrote: “I violated the laws of Victorian propriety. I worked for a lifetime to break down the prejudice against women, to prove that we could do the things men did, and it was not until I became an old woman that I realised that I had succeeded.” These travellers were viewed as exceptions by their contemporaries, male and female.

But travel influencers owe part of their popularity to relatability. The photographs and videos they upload are aspirational, but with the implicit message that this lifestyle is accessible to their followers. This can be emotionally damaging to social media users who cannot afford to travel. It is, less intuitively, even damaging to those who can. A Wells Fargo study targeting 1,000 Millennials earning at least $250,000 per year revealed that 59% prioritise spending that makes them appear financially successful, and more than 40% rely on credit cards and loans to do so.

Influencer travel habits aren’t accessible to the general public for myriad reasons. For one, creators often don’t pay for their travel - the cost is covered by brands and tourism boards. They get access to experiences that may be off-limits to others. On top of this, the most visible and admired influencers often make higher-than-average incomes. All this is compounded by the fact that influencer-created images are highly edited and idealised, as we have already discussed.

The penultimate differentiator is self-presentation. In a paper published in 2022, Lauren Siegel, Iis Tussyadiah and Caroline Scarles describe travel photography as a form of online impression management. They write that “there has been a shift in personal photography such that photos are used to construct one’s idealised identity, which is contrary to past photographic practices as a form of memory documentation”. This echoes my previous distinction between the private and public consumption of travel images. But the researchers go deeper.

I’m fortunate to know Dr Lauren Siegel, Senior Lecturer in Tourism and Events at the University of Greenwich, personally and she let me interview her for this piece. We discussed how social media has not only made sharing photographs easier - it has changed social behaviour. Travel photographs have become an integral part of our identities. We now treat travel as an economic good, and travel photographs as a form of conspicuous consumption that signals status, taste, and cultural capital. The trip is no longer just for the traveller, it’s for the audience.

As Dr Siegel writes in another paper, co-authored in 2018 with Dan Wang: “A marker of social status may no longer be material or physical in nature; as someone at the turn of the century might have shown their social status by purchasing a piano for their home, or someone in the 1950s might have installed a swimming pool for their suburban neighbours to envy, today’s millennial consumers represent their social status by posting photos of themselves in Thailand or other “exotic” locations.” Influencers are idolised by their audiences precisely for their ability to consistently produce these aspirational visuals.

Even fifteen years ago, watching someone film or photograph themselves in public might have elicited stares. Nowadays there is an unspoken assumption that the individual is capturing social media content. Creators like Sabrina Basson, known as Tube Girl, occasionally spark a debate about the extent to which we should normalise this behaviour. But a few eye-rolls notwithstanding, self-shooting content in public is increasingly normalised. This applies to professional influencers, aspiring creators and even private individuals.

What is perceived as aspirational naturally changes over time. Dr Siegel views this topic through a generational lens. If you’ve been doing some mental math you already know I’m a millennial - a zillennial, to be specific. The aesthetic I adhered to in 2016, epitomised in our opening Paris scene, is no longer dominant. In 2025, Gen Z and Gen Alpha are in the driving seat and they are “very good at spotting inauthenticity”, in Dr Siegel’s words. More active on TikTok than Instagram, they’ve forged their own aspirational aesthetic which leans more heavily on raw video content.

But Gen Z is also increasingly plagued by beauty sickness. In the aforementioned Girlguiding report from 2024, 61% of female respondents aged 11-16 said they wanted to change their appearance by losing weight, compared to 51% in 2018. Weight loss is not the only body image “trend” on the rise. When it comes to cosmetic surgery, more than 9 million Botox treatments were administered globally in 2022. That represents a 26.1% increase in just one year. During that same year, cosmetic procedures had risen by 102% from the previous year in the United Kingdom. Gen Z and Gen Alpha may prefer seemingly authentic content, but that doesn’t mean social media pressures are fading. On the contrary, they seem to be intensifying.

Algorithmic reinforcement is the fifth and final differentiator on my list. Social media algorithms prioritise content that gets the most engagement in the form of likes, shares and watch-time. In photography, this primarily comes down to aesthetics. But all the following trends are also present in video content, which has surpassed static images in popularity with the rise of TikTok.

A 2020 study found that pictures with human faces can increase engagement by 38% to 291% on Twitter. Instagram influencers recognised this early, making people-centric images their main focus. Dr Siegel and her colleagues found that 75% of the travel influencer photographs they studied featured a single subject and just 1.65% focused entirely on landscape with no human subject. They also noted a tendency for exaggerated outfits, often impractical for the activity portrayed.

Images that focus on attractive people perform particularly well. A study published in Infant Behavior and Development found that infants as young as a few days old tend to look longer at faces rated by adults as attractive, in contrast to those rated as unattractive. This preference extends beyond human faces - a later study published in Developmental Science showed that 4-month-old infants preferred attractive over unattractive cat faces. Humans seem to have an innate preference for aesthetically pleasing visuals.

As a result, aesthetically fine-tuned images are often those that receive the highest levels of engagement. That leads creators to optimise not only their images but their own selves, as evidenced by surging cosmetic surgery rates. The algorithm rewards these efforts and reinforces the vicious cycle.

So who is to blame?

Feeling angry at influencers for setting unrealistic expectations is understandable. But before we judge too harshly, let us consider what the data tells us. Social media algorithms - guided by consumer engagement patterns - favour aesthetically pleasing images of aesthetically pleasing people. Influencers shoot and edit their images to optimise for engagement. As a result of their optimisation, they get rewarded with further reach, allowing them to connect with more users and grow their audience. The wheels on the bus go round and round.

This aesthetic narrative isn’t just pushed by influencers, it trickles down to their audiences. According to a survey of 2,000 social media users, 39% of Americans pretend to be influencers while on vacation. This behaviour encompasses photography, captions and even fully edited vlogs. Nearly a quarter (23%) of those surveyed reported feeling disappointed when their vacation content didn’t get as many likes as they had hoped. Amongst travel influencers that figure would, of course, sit closer to 100% as their incomes and identities become entangled with audience engagement.

Travel influencers are thoroughly steeped in the toxic brew of social media, spending hours on these platforms every day to observe emerging trends, interact with audiences, edit and post content. Influencers are particularly at risk of internalising mainstream aesthetics. My own life has been an excellent case study. Although I am acutely aware of all the work that goes into creating the perfect image, I am no less susceptible to its harmful effects. Despite being an ardent feminist and a proponent of body neutrality, I have spent many midnights doom-scrolling and wondering whether I should have beautifying toxins injected into my skin. I spend too much time on social media to avoid being indoctrinated by it, on some level.

Influencers don’t create aspirational images to make others feel inferior. Influencers simply respond to market demands and their own internalised beauty standards. Consumers, in turn, rely on those same internalised norms when deciding which content to consume. Depressing as it seems, influencers and consumers are all complicit in this vicious cycle.

Profit-driven platforms offer no help because they don’t care about our well-being. These corporate entities care about the bottom line, which relies on users’ continued engagement, not their mental health. In fact, negative mental health and body image can be immensely profitable by increasing sales of goods marketed as remedies - goods created by companies who pay these social media platforms to boost their advertising content.

Many travel content creators are deeply impressive women. Many share valuable information, approach their photography with a rigorous work ethic and bring awareness to important causes. But, for the most part, the primary aesthetics of travel content are not empowering. Social media travel images simply tend to echo the mainstream ideal of femininity, rooted in Western whiteness and privilege, against the pleasing backdrop of various foreign countries.

Where do we go from here?

I’ve returned to social media, since quitting in 2018, and made it my primary career once again. I’ve distanced myself from the idealised travel images I used to post and now focus on video content, which lends itself more easily to authenticity. I actively try to “de-influence” my audience with frequent reminders of the time, work and editing that goes into producing even the most casual-looking posts.

But I don’t want to overstate my impact. My perspective is that of a compassionate human being, but it is also the perspective of a white, conventionally attractive, relatively young and privileged woman. In many ways, I continue to benefit from the same dynamics I critique.

Despite my attempts at fostering empowerment, I’m still forced to tiptoe along the edge where transparency and visibility meet. This ongoing tension reflects the paradox of social media authenticity. Even though I challenge the idealised aesthetics that once permeated my online content, I do so using platforms that continue to reward them. And when I optimise my content for engagement, I do so by playing up to the algorithm. Despite attempting to “keep it real” I remain a participant in the very spectacle I question. The irony is not lost on me.

I don’t have all the answers, but I do have a few suggestions. First and foremost, we need to go out of our way to engage with content that subverts mainstream aesthetics. Social media content simply repeats our society’s dominant power dynamics - centring whiteness, glamorising certain body types and even romanticising poverty. It is our responsibility to seek out points of view not favoured by the algorithm. Influencers who are not white, not able-bodied and not otherwise privileged are less likely to get mainstream attention. But we desperately need diverse perspectives. Encountering them is the first step toward critically assessing our aesthetic preferences and challenging them.

Additionally, we should limit the time we spend on social media. A 2022 study of girls aged 10-19 showed that a three-day social media break lowered their body surveillance, shame and boosted their self-compassion. A 2018 study from the University of Pennsylvania similarly demonstrated that limiting social media to 30 minutes a day improved participants’ mental health.

Finally, we should continue to deepen our understanding of the historical, political and cultural forces that shape social media images. There is so much to be gained from listening to points of view outside of our own - this essay is merely one woman’s attempt to start that conversation.

I welcome your feedback, so please leave me a comment and share your perspective. You can also find me on Instagram - but you already knew that.

Sources

(in order of appearance)

https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/egypt-zangaki-brothers-1870-1890/

https://www.getty.edu/publications/resources/virtuallibrary/9781606060353.pdf

https://fi.edu/en/science-and-education/collection/kodak-brownie-camera

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Daughter-Desert-Remarkable-Life-Gertrude/dp/0330431579

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Gertrude-Bell-Arabian-Diaries-1913-1914-ebook/dp/B00TRDD38M

https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2012/02/vita-fanny-bullock-workman

https://www.vivianmaier.com/about-vivian-maier/

https://vivianmaier.blogspot.com/2009/10/unfolding-vivian-maier-mystery.html

Lynd, Robert. "The Travel Album: A Social Document." The New York Times, 1953.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Tourist-New-Theory-Leisure-Class/dp/0520280008

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Beauty-Sick-Cultural-Obsession-Appearance/dp/B06XC76N1J

https://www.socialpilot.co/instagram-marketing/instagram-stats

https://studyfinds.org/young-women-edit-photos-online/

https://nypost.com/2024/02/15/business/most-millennials-think-its-important-to-appear-rich-study/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13683500.2022.2086451

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10548408.2018.1499579

https://www.spamedica.com/blog/botox-usage-statistics-2023/

https://baaps.org.uk/about/news/1872/cosmetic_surgery_boom/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32680294/

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2566458/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1740144522001589

https://www.businessinsider.com/facebook-instagram-snapchat-social-media-well-being-2018-11

Love this well researched piece! I work with people with eating disorders and have to encourage reduced time on social media and active 'management' of the algorithm like you said. People with EDs are over 300% more likely to be shown diet and body checking content online which is pretty horrific. I write about these sorts of topics on my publication if you want to check it out :)

Enjoyed how you zoomed out and back to ground us in the context of travel photographs, and then a second time in the data related to influencing. Your hard work and conscientiousness is getting these right — and citing your sources — is appreciated!